Guides / How are Select Committee Chairs elected?

The Chairs of most House of Commons Select Committees are elected by the whole House, by secret ballot, using the Alternative Vote system.

For each Government Department, the House of Commons has a dedicated departmental Select Committee to scrutinise it. But changes to the line-up of Select Committees, to reflect machinery-of-government changes to Departments, do not take place automatically. There is some scope for discretion and negotiation – with, in practice, the Government ultimately deciding whether and how to make changes.

The principle that each Government Department would have a dedicated House of Commons Select Committee to scrutinise it was at the heart of the creation of departmental Select Committees (DSCs) in 1979. It has been set out since then in Standing Order No. 152. The principle means that when a new Government Department is created, or the remit of an existing Department changed, the House of Commons must make changes to its Select Committees so that the Department has a corresponding Select Committee.

However, when the line-up of Government Departments is changed, the process of making corresponding Select Committee changes is not automatic. To create or abolish a Select Committee, or change the name or remit of an existing Committee, the House must amend its Standing Orders. (The motion to do so will in practice be tabled by the Government, and is amendable.) And there is no bar to the House having a line-up of ‘departmental’ Select Committees which does not, in fact, map exactly onto the list of Government Departments: while each Government Department has its own Select Committee, the House may decide to have other Select Committees too.

This means that when the line-up of Government Department changes, there is some scope for discretion and negotiation about the way in which the change is reflected among Select Committees. For example:

when the Department for International Development (DFID) was abolished in 2020, the International Development Committee (IDC) survived (after MPs campaigned successfully to get the Government to abandon its initial plan to abolish it);

the Exiting the EU Committee and its successor, the Committee on the Future Relationship with the EU, similarly existed through to January 2021 after the Department for Exiting the EU (DExEU) was abolished a year earlier; but

There is no deadline, following changes to Government Departments, by which the House must make the corresponding changes to its Select Committees.

When the Government creates a new Department, there are broadly two possible ways of changing the Select Committee line-up to reflect this.

This is achieved by:

The Chairs of most House of Commons Select Committees are elected by the whole House, by secret ballot, using the Alternative Vote system.

having the House agree a motion that “all proceedings of the House” concerning the existing Committee – including the appointment of Members and the election of the Chair – should be understood as applying to the Committee under whatever new name it is to be given; and

amending Standing Orders to change the name and remit of the Committee to reflect the new Department.

The most visible implication of this option is that the Chair and Members of the existing Committee remain in place and there is no election for a new Chair.

Some examples of this process are given in the table below.

Conversions of existing Select Committees into Select Committees for new Government Departments: Some examples, 1997-2023

| Government Department change | Select Committee change | |

|---|---|---|

| Feb-March 2023 | Department for Business and Trade (DBT) created by merging parts of former Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), which was broken up, with Department for International Trade (DIT) | Previous Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) Committee converted into Business and Trade Committee (BTC); International Trade Committee (ITC) abolished |

| Feb-March 2023 | Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) created by merging parts of former Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) (including Government Office for Science) with parts of former Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DMCS) | Previous Science and Technology Committee (STC) (which scrutinised Government Office for Science) converted into Science, Innovation and Technology (SIT) Committee |

| July-Oct 2016 | Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) created by merging former Department for Energy and Climate Change (DECC), which was abolished, with parts of former Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) | Previous Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) Committee converted into Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) Committee; Energy and Climate Change Committee abolished |

| June 2009 | Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) created by merging Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform (BERR) with Department of Innovation, Universities and Skills (DIUS) | Previous Business and Enterprise Committee converted into Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) Committee; previous Innovation, Universities, Science and Skills Committee converted into Science and Technology Committee (STC) (to scrutinise Government Office for Science) |

| May-July 2007 | Ministry of Justice created by merging Department for Constitutional Affairs with parts of Home Office | Previous Constitutional Affairs Committee converted into Justice Committee |

This is achieved by adding the new Committee to the list of departmental Select Committees in Standing Order No. 152.

This option means that Members must be appointed to the new Committee and an election held for its Chair.

The table below gives some instances of new Select Committees being created following the creation of new Government Departments.

New Select Committees created following the creation of new Government Departments: Some examples, 1997-2023

| New Government Department or other innovation | New Select Committee | |

|---|---|---|

| Feb-March 2023 | Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) (created from energy portfolio of former Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS)) | Energy Security and Net Zero |

| July-Oct 2016 | Department for International Trade (DIT) | International Trade Committee (ITC) |

| July-Oct 2016 | Department for Exiting the EU (DExEU) | Committee for Exiting the EU ('Brexit Committee') |

| May-June 2010 | Nick Clegg MP appointed Deputy Prime Minister with responsibility for political and constitutional reform | Political and Constitutional Reform Committee |

| Oct 2008 | Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC) | Energy and Climate Change |

| May-July 1997 | Department for International Development | International Development Committee (IDC) |

Some Select Committee changes to reflect machinery-of-government changes are uncontroversial – if a Department gains or loses a relatively minor policy area without changing its essential profile, and its name is altered accordingly, it is usually relatively straightforward for the Select Committees to follow suit.

However, sometimes, decisions about departmental Select Committee changes can be politically charged. If a departmental Select Committee is abolished, the Chair loses their position and the additional salary that goes with it. If a new Committee is created without an existing Committee being abolished, the overall number of Committees will rise and an argument may be triggered about which party is entitled to the new chairship. There may also be concerns about the availability of MPs to serve on an additional Committee, and about the extra staffing and other costs involved.

13:15, 24 April 2023

Hansard Society (2023), What happens to Select Committees when Government Departments change? (Hansard Society: London)

MPs will debate the fourth anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine; changes to the Charter for Budget Responsibility; student loan repayments; support for bereaved children; and St David’s Day. They will also consider the Armed Forces Bill, the Industry and Exports (Financial Assistance) Bill, and the Cyber Security and Resilience (Network and Information Systems) Bill. Cabinet Ministers Steve Reed, Wes Streeting, Douglas Alexander, and Lisa Nandy face departmental questions. In the Lords, Peers will scrutinise the Tobacco and Vapes Bill, the Crime and Policing Bill, and the National Insurance Contributions Bill, alongside debates on UK–EU relations and transnational repression. Select Committees will question the Bank of England Governor, former OBR chairs, standards regulators, and Ministers, including an inquiry into trade sanctions.

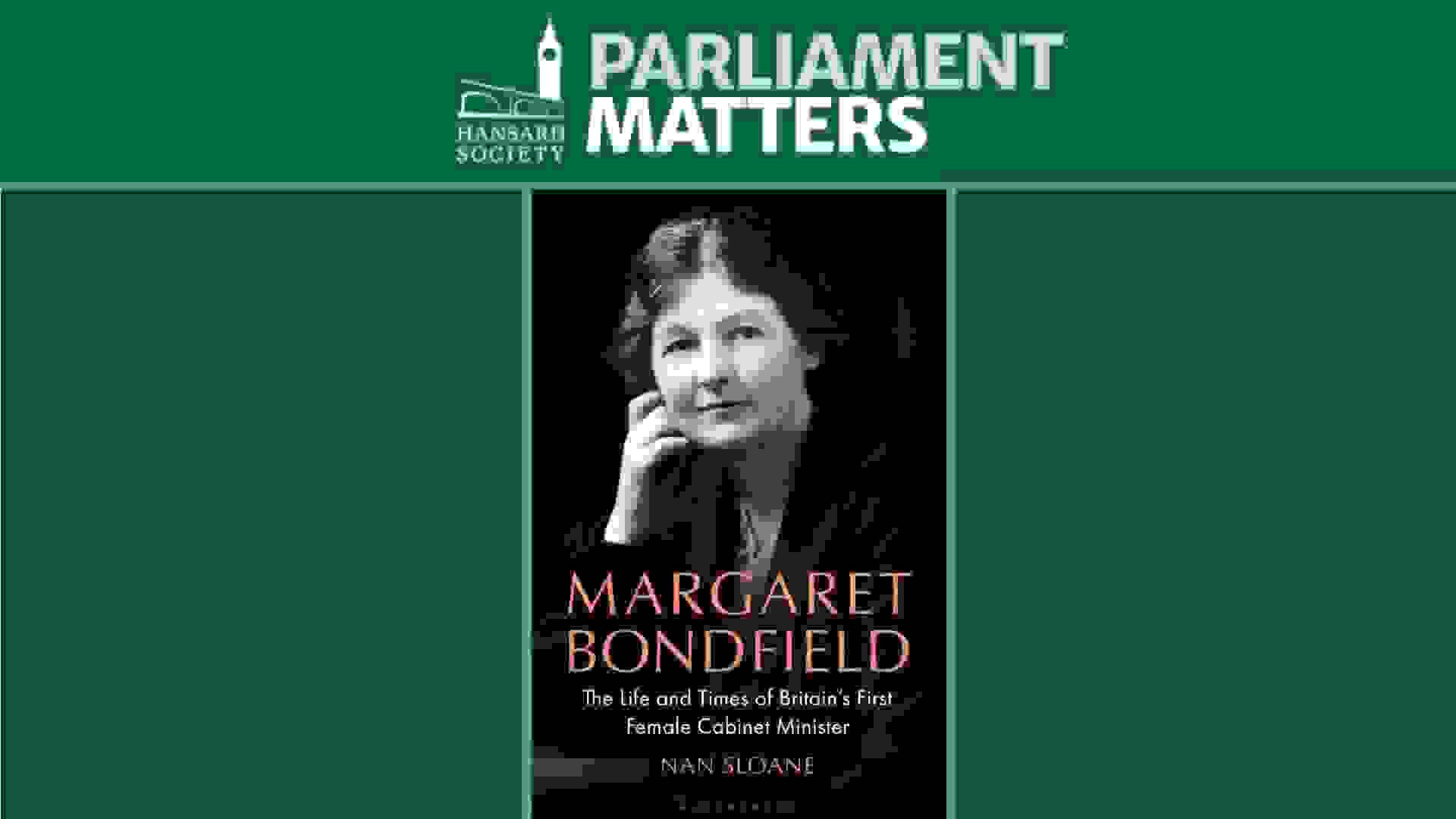

Why is Britain’s first female Cabinet Minister largely forgotten? Historian Nan Sloane discusses her new biography of Margaret Bondfield, the trade unionist who became the first woman in the British Cabinet. Rising from harsh shop-floor conditions to national prominence, Bondfield took office as Minister of Labour in 1929 at the onset of the Great Depression. As economic crisis split the Labour Party, her reputation never recovered. Was she a pioneer, pragmatist, or unfairly judged? Listen and subscribe: Apple Podcasts · Spotify · Acast · YouTube · Other apps · RSS

On the fourth anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Dr Sarah Whitmore will be speaking to us about how the Ukrainian Parliament has functioned under wartime conditions. 6:00pm-7:30pm on Tuesday 24 February 2026 at the Houses of Parliament, Westminster

Labour MP Neil Duncan-Jordan reflects on rebelling against the whip and calling for Keir Starmer to resign, as we assess the fallout from the Mandelson–Epstein affair and its implications for the Government’s legislative programme and House of Lords reform. We examine Gordon Brown’s sweeping standards proposals, question whether they would restore public trust, revisit tensions over the assisted dying bill in the Lord and discuss two key Procedure Committee reports on Commons debates and internal elections. Listen and subscribe: Apple Podcasts · Spotify · Acast · YouTube · Other apps · RSS

The Restoration and Renewal Client Board’s latest report once again confirms what Parliament has known for nearly a decade: the cheapest, quickest and safest way to restore the Palace of Westminster is for MPs and Peers to move out during the works. The “full decant” option was endorsed in 2018 and reaffirmed repeatedly since. Remaining in the building could more than double costs, extend works into the 2080s, and increase risks to safety, accessibility and security. With the Palace already deteriorating and millions spent each year on patchwork repairs, further delay would itself be an expensive course of action, one that defers decisions without offering a viable alternative.